Going to change things up a little for this Historical post, as today I’ll be starting a 3 blog series talking about the doctrine and tactics of each planned nation. We’ll be covering the American infantry, German line and panzer grenadier infantry, and British armoured and line infantry. This week, the German Army.

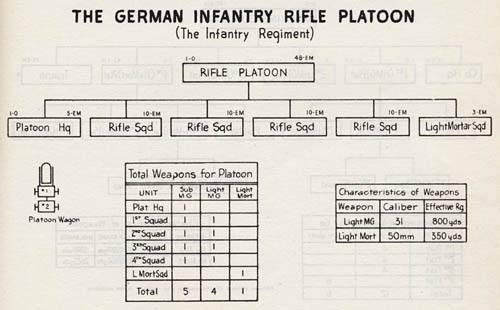

The German Infantry Platoon

The German infantry platoon tends to operate the same way as an infantry platoon in any other army of the 1930s & 1940s – The platoon has 3 (sometimes 4) sections, as above, and a light mortar which in practice is attached to the platoon headquarters. The platoon leader tends to be an officer, usually a Leutnant, although it is not uncommon especially in the German army of the period for warrant officers to be platoon leaders. It has its own transport: for line infantry horse and cart, for Panzer Grenadiers a light truck, nominally an Opel Blitz.

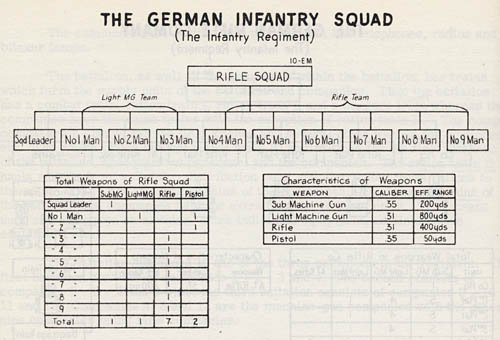

The German Infantry Section

The infantry section in the German army, whether it is Panzer Grenadier or Schutzen, is 9 men strong. It consists of 5 riflemen supporting a 3 man machine-gun team with a section leader managing the movements of the whole. German strategists realised after analysing the performance of the infantry in the First World War that a well-trained machine-gun team were arguably a more valuable resource than 10 riflemen due to the fact that crews were less likely to fall prey to covering instead of firing. The establishment of buddy teams manning the machine-gun also added to the effectiveness, as the men would know and like each other, not wanting to let each other down.

As such, the axis of offensive action for German infantry revolves around the machine-gun within the squad, and the role of the riflemen within a squad is to support the machine gun, not vice versa. The role of the machine-gun is to fix the enemy, and eliminate them through superior fire if possible. If this cannot be achieved, the enemy is suppressed until the rifleman supporting the machine gun can close to grenade and bayonet range, and eliminate the enemy that way.

German Soldiers of the 709 Infantry Division, abandon their refuge and rush to their positions in Montebourg, Normandy in June 1944.

The Wehrmacht in Normandy in this regard is not too different to the Wehrmacht of the early war exploits, trained to be taking the fight forever to the enemy, meeting attack with counter-attack, advance with counter-charge and the like. Panzer Grenadiers, the infantry trained specifically for close operation with German armoured formations, tended not to operate any differently to their regular Schutzen counterparts, other than moving close to the enemy by trucks or halftrack as part of a wider offensive before dismounting and fighting.

The OSS produced a film to educate their agents on the way German infantry fought. It’s a fantastic period source to show how the Americans in particular understood the doctrinal requirements of the German Army.

Co-operation with other arms

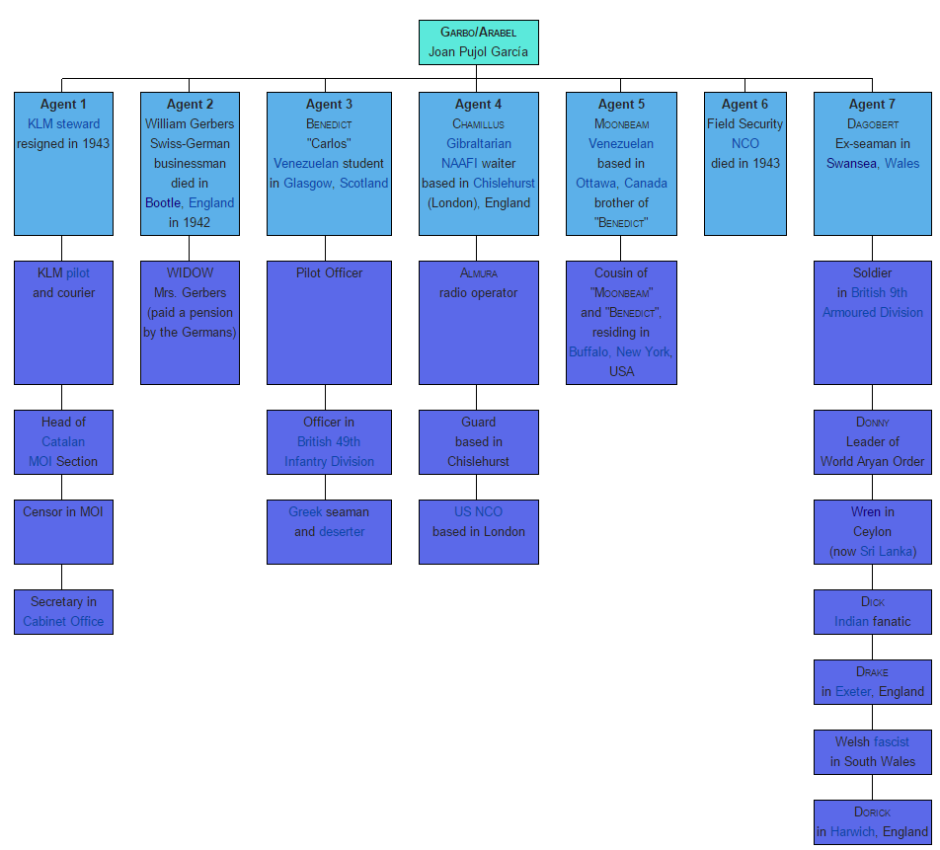

German infantry tended to grasp inter-arm co-operation a lot better than the British or American infantry did, especially earlier in the war. German infantry and armour commonly worked together in both training and combat, meaning that commanders of both branches often knew enough of their counterpart role to complement each other in the attack. These ‘Kampfgruppen’ were generally thrown together from units the same general area to complete a specified task, i.e. the defence of a strategic locality or for an offensive action.

The Kampfgruppe was essentially a mish-mash of different branches (armour, artillery, infantry etc) organized quickly in accordance with tactical and strategic situation at hand. Kampfgruppen were usually named for the superior officer, and they are exceedingly common in in Normandy as infantry fought pitched battles with the resources they had to hand. Although very little official doctrinal texts survive concerning them, they occasionally pop up in unit war diaries and in the regimental and official histories of the units concerned.

Next Week: American infantry doctrine in Normandy